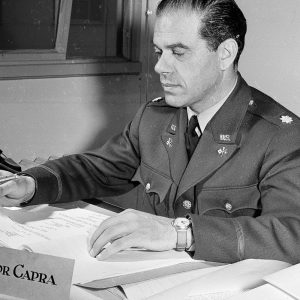

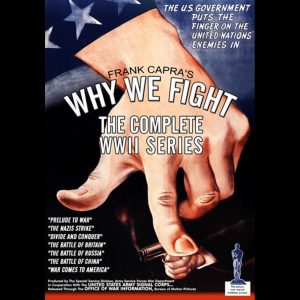

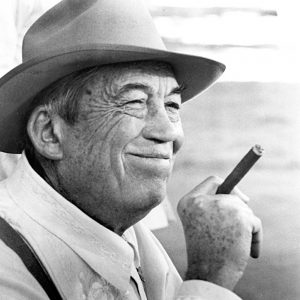

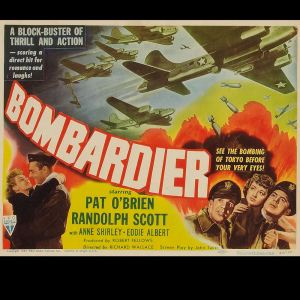

In 1945, as the war wound down, Capra, Ford, Wyler, Huston, and Stevens returned to Hollywood. What use could they make, as newly reborn feature filmmakers, of what had happened to them? The work of all five deepened, or at least got weightier, after the war. Ford shot a beautiful and leisurely picture, “They Were Expendable,” about the small PT boats (commanded by Robert Montgomery and John Wayne) that harassed Japanese ships in the Philippines during that anxious spring of 1942. The film is suffused with an elegiac melancholy that is unique in American movies. Ford, as he did in “Midway,” embraces a moment of vulnerability: the Americans lose not only a military campaign but a much loved colony, which is evoked as a gentle, palm-treed heaven, where officers in Navy whites and grizzled seamen commingle with respectful Filipino helpers. Politically, Ford’s imperialist nostalgia doesn’t pass muster, but “They Were Expendable” is free of the crudely righteous anger and patriotic tub- thumping common in such movies as the 1945 Errol Flynn vehicle, “Objective, Burma!,” and it remains the most emotionally satisfying of Second World War combat films. Wyler filmed the ravaged coast of Italy from the open fuselage of a B-25, and, as a result, permanently lost most of his hearing. He had been away from Hollywood and his family for three years, and when he returned, handicapped, he found himself ill at ease. His producer, Samuel Goldwyn, owned the rights to a Time article about a group of marines on leave. The novelist MacKinlay Kantor first worked on the screenplay; then the playwright Robert E. Sherwood, who had been one of F.D.R.’s speechwriters, took over. Wyler joined him and together they developed a screenplay about three vets returning to a Midwestern city: an Army sergeant (Fredric March), who has trouble settling back into his life as a banker; an Air Force bombardier (Dana Andrews), who can’t find a good job or hold on to his wife; and a young sailor (Harold Russell), who has lost his hands and shrinks away from his girlfriend. “The Best Years of Our Lives,” as Wyler’s masterpiece came to be called, is a surprisingly dissonant portrait of homecoming, in which the cheerful American surface is consistently punctured by disappointment and dread. Much of what Wyler had gone through, Harris writes, was fed into the experience of the three men. At the climactic moment, Andrews’s flier walks through a field of discarded B-17s, and is overwhelmed by memories of bombing runs that went bad. The camera bores in; the bombardier sweats and then relaxes. For him, Wyler implies, the war may finally be over—as it was, perhaps, for Wyler, too. He picked up his career where he had left off. John Huston, racked by memories of the devastation of San Pietro, made a documentary about soldiers suffering from trauma, “Let There Be Light,” which was shot in a psychiatric hospital on Long Island. The film so upset the Army that it kept the movie out of the public view for decades. Huston’s determination to face the worst—his “sardonic cynicism,” as Harris calls it—colors Humphrey Bogart’s famous performance and everything else in the first feature that Huston made after the war, “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.” Huston had a long and illustrious postwar career. Stevens did, too, but in some ways he was a casualty of the war. Shaken and demoralized when he got home, he kept to himself, drank heavily, and didn’t work for several years. In the nineteen-fifties, he reëmerged as the director of large-scale productions with important-sounding titles and themes: “A Place in the Sun,” “Shane,” “Giant,” and “The Diary of Anne Frank.”

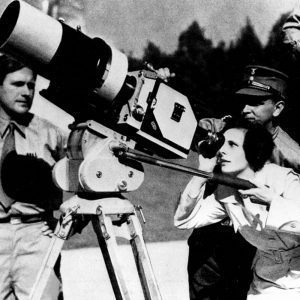

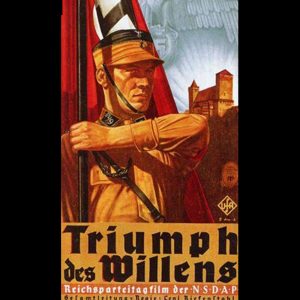

“It’s a Wonderful Life” was nominated for five Oscars but was a box-office flop—a failure from which Capra never really recovered professionally. In the end, however, the film became a double triumph for him. It grew to be one of the most beloved of American movies, and, as such, it provided his final answer to the Riefenstahl film that had troubled him so many years earlier. Capra created his own myth—not a self-immolating ecstasy of national greatness through purity and death but a garrulous and funny portrait of what a good life might mean in an American town. Family, friends, economic struggles, neighborly help, good cheer: the movie exudes an almost hysterical desire for ordinary happiness. “It’s a Wonderful Life,” with its mawkish benevolence, felt out of date in the notorious forties, but its vision of a democratic community, seen now, seems like something for which Americans would have gone to war.